streets.mn

“As the Twin Cities proceeds with plans to build over three billion dollars worth of rail extensions for the Blue and Green Lines, many transit advocates question if we’re missing an opportunity for transformative projects that lift up urban neighborhoods on their routes between suburban park & rides and the downtown core...

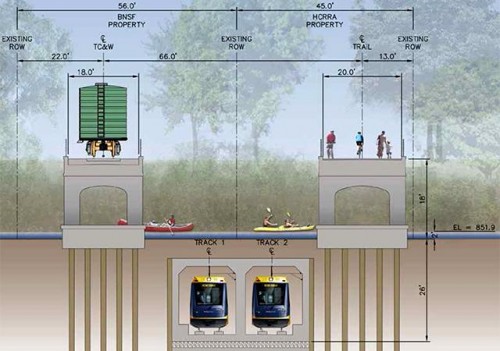

It comes down to this: Let’s discuss costs and benefits in parallel until shovels hit the ground, rather than committing to a “value” alignment and then being all ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ when the cost goes up 50% or more. For things like tunnels under parks and bridges over the Grimes Pond which are being planned precisely because these low-development corridors were supposedly going to make the chosen alignment more cost effective. If we’re going to build viaducts and tunnels, let’s at least do it in a way that brings stations to the doorsteps of tens of thousands more transit riders.”