Seattle News:

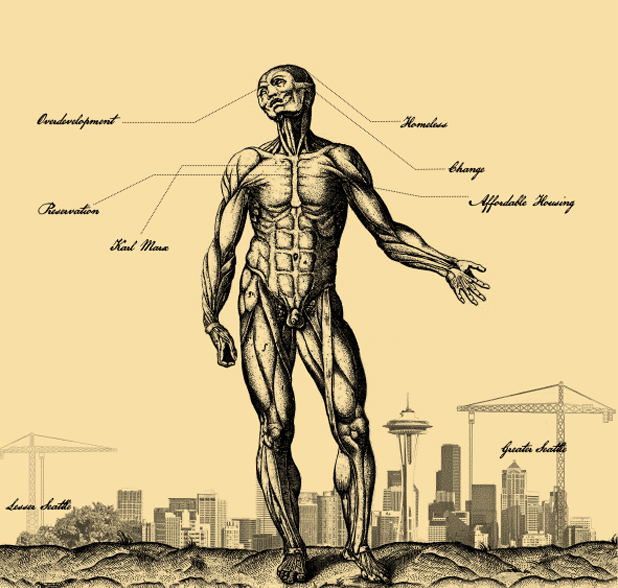

“The language is apocalyptic; the tone, desperate. “Cancer,” “canyons of darkness,” “anguish, hopelessness, and loss.”

But these aren’t war-zone dispatches, nor recollections of a natural disaster. They’re public comments from a Seattle City Council’s land-use-committee hearing held earlier this year. It was there that aggrieved homeowners walked up to one of two smooth wooden podiums in City Hall’s Council chambers to vent the vexation they felt as they watched their communities “being torn apart” by development, as Capitol Hill resident the Venerable Dhammadinna put it.

“Elderly homeowners, the gay community, older women, and families are no longer welcome,” she told the Council, referring to the city’s mixed-density residential areas. “Our neighborhoods are shadowed by tall, bulky buildings. Gardens are being cemented, trees cut down. Those who can’t carry their bags of groceries up and down the hills are not invited into this dystopia.”

The testimony was so consistent—or redundant, depending on your position—that a drinking game could have been fashioned from the proceedings: Take one shot whenever someone said “neighborhood character,” two for “transient.””

An interesting article of Seattle redevelopment dynamics and politics. I was struck by the sameness of the issues across many places.