Works in Progress

“When it comes to stories of progress, there aren’t many environmental successes to learn from. We’ve seen massive improvements in many human dimensions in recent decades – declines in extreme poverty; reductions in child mortality; increases in life expectancy. But most metrics that relate to the environment are moving in the wrong direction. Although there are some local and national successes – such as the large reductions in local air pollution in rich countries – there are almost none at the global level.

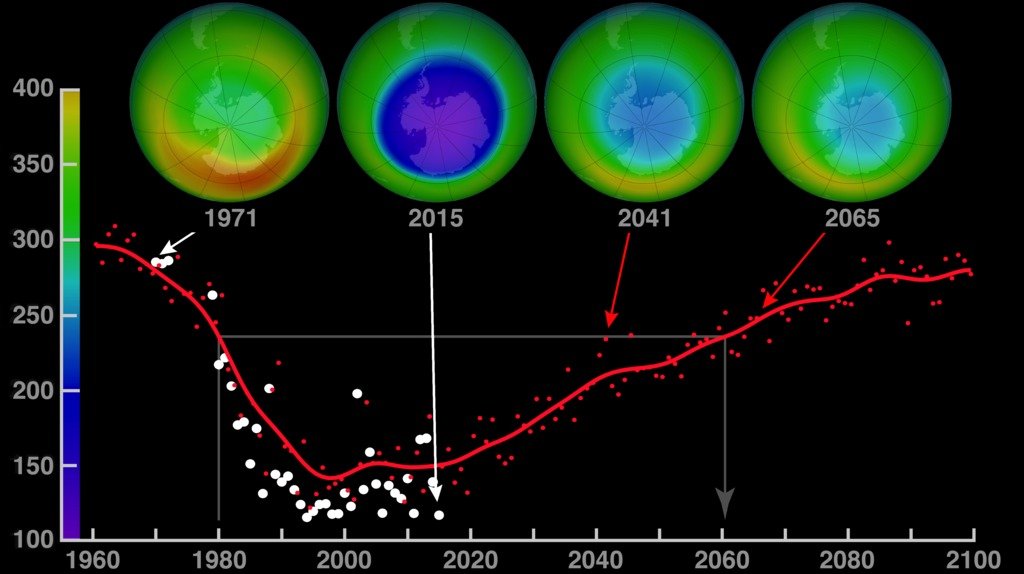

Yet there is one exception: the ozone layer. Humanity’s ability to heal the depleted ozone layer is not only our biggest environmental success, it is the most impressive example of international cooperation on any challenge in history...

Our efforts to tackle other environmental problems have not been quite so successful. Can we extrapolate any of the lessons from the task of fixing the ozone layer to other challenges, such as climate change?

There are of course many similarities: ozone depletion and climate change are shared, global problems. Unlike air pollution where local residents are impacted by local emissions, it is the entire global population that is impacted by ozone depleting substances and greenhouse gas emissions. This is because these gases disperse easily across the globe; they are known as ‘well-mixed’ gases. The need for international coordination on both issues is therefore obvious.

We can also learn from the ramping up of efforts over time. The ambition of the first Montreal Protocol in the 1980s was far too weak to solve the problem. Although it was better than ‘business as usual’, the target would have meant that the ozone hole would have continued to expand. Our efforts were only successful because we continued to raise the standards of regulation over time. Climate policy is in a similar position today, and has been for a long time.”