CityLab:

Robert Fullerton: Getty

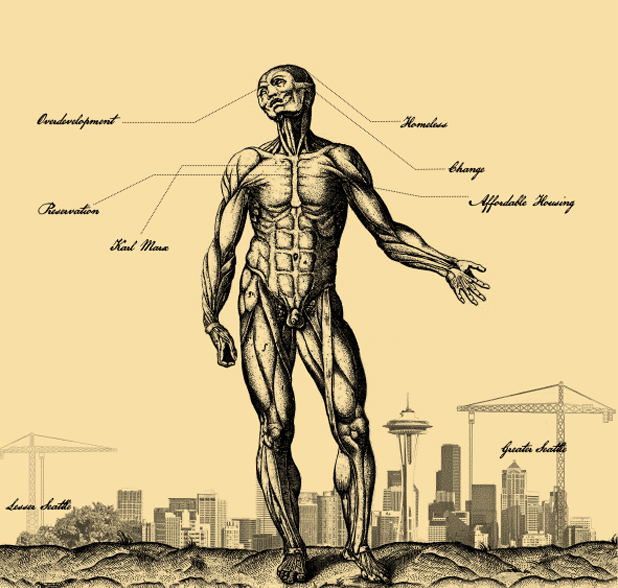

“Social scientists broadly agree that bans on multifamily housing are bad for housing affordability, bad for racial inequality, and bad for the environment. Yet there has been a broad political consensus that changing these long-entrenched policies is out of the question. In neighborhood debates about planning and zoning policy, the loudest voices usually belong to people who are satisfied with the status quo. The vaguest of not-in-my-backyard objections from wealthy homeowners—who attend public meetings and regularly vote—are often enough to thwart the construction of new housing.

What’s happened in Minneapolis is different—and so unusual that my colleagues at the Century Foundation and I undertook a detailed review of how and why reformers prevailed. In Minneapolis, housing advocates have succeeded by shifting the focus of public discussion toward the victims of exclusionary zoning. More important, advocates also showed public officials and their own fellow citizens just how numerous those victims were.

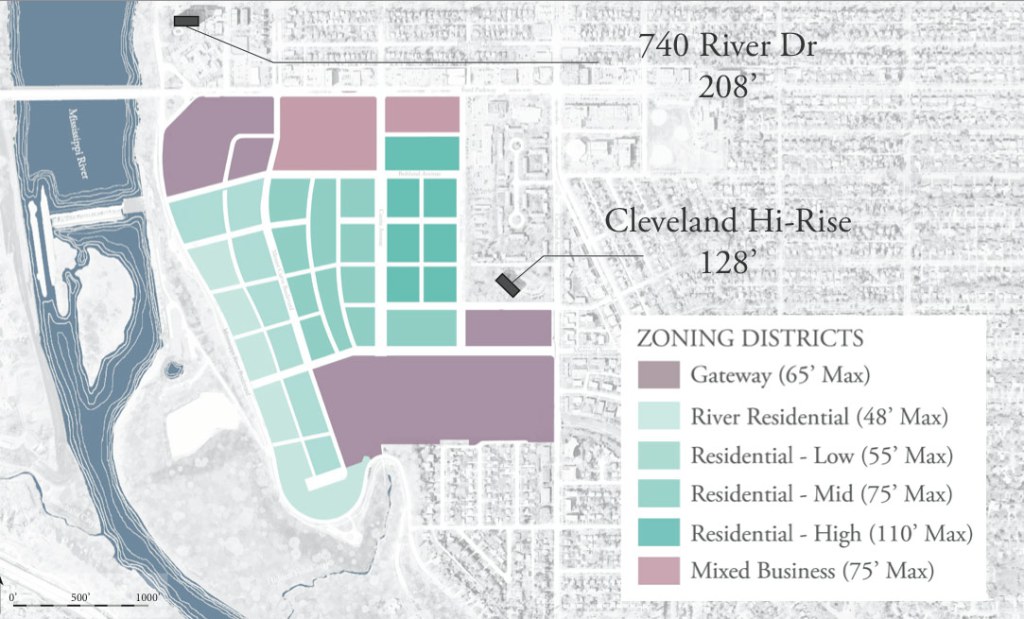

Despite being a city of 425,000 residents, Minneapolis until now has banned duplexes, triplexes, and larger apartment buildings from 70 percent of its residential land; in New York City, by comparison, just 15 percent of residential land is set aside for single-family homes. The city council’s Minneapolis 2040 plan up-zones the city to allow two- and three-family buildings on what had been single-family lots, tripling the potential number of housing units in the city.”

This new zoning law is now the standard in Minneapolis. See City Pages